Cash on the Shelves: A Deeper Dive Into How Shops Manage Parts, Inventory Counts, And More

Your parts inventory is cash on the shelves.

Or, in the words of Irvin Bowman of Truck Shop Network, “A shop lives or dies based on how they handle parts.”

Parts have always been a critical element of repair shop business, but man, that quote has never been timelier. Thanks to the global pandemic and the ensuing supply chain issues, parts are harder to get than ever—but alas, your customers don’t stop needing parts just because you can’t get them, or can’t find them, or aren’t pricing them correctly.

Not surprisingly, our 2022 edition of the State of Heavy-Duty Repair took a closer look at the parts shortage, and how shops handle inventory in general. We discovered the following:

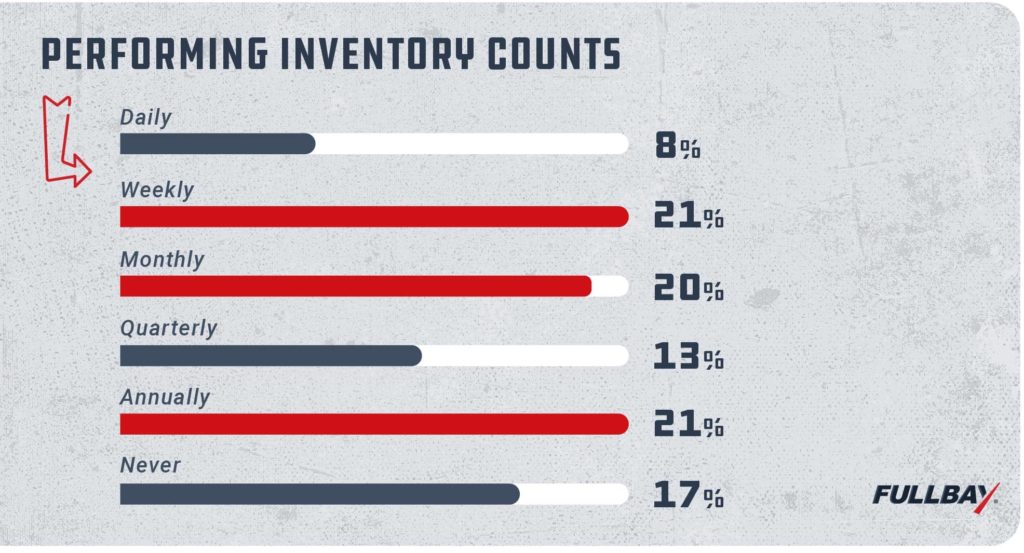

- About half of all shops are performing an inventory count of some sort—once a week, once a month, or daily.

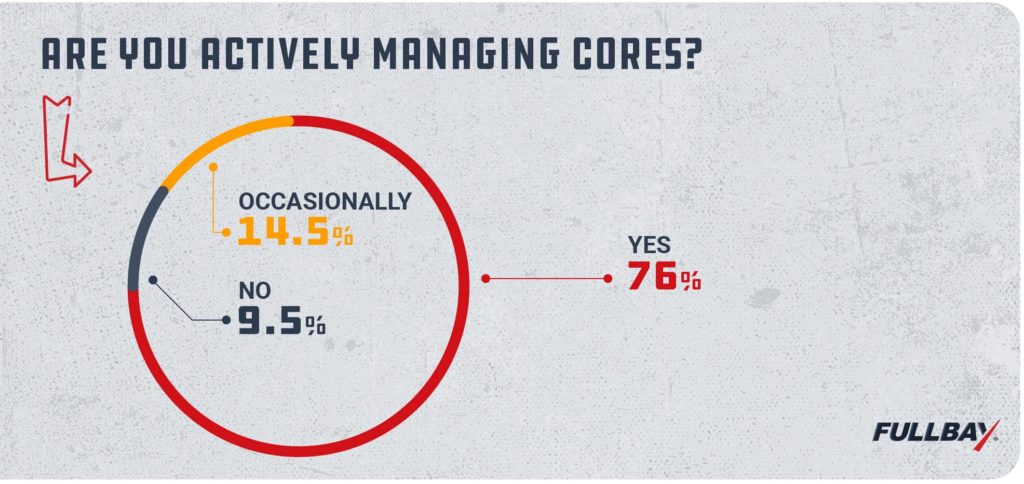

- 76% of shops are managing their cores…but 9.5% aren’t touching them at all.

- 44% of our respondents only have the parts they need in inventory a quarter of the time.

It was all fascinating information…but it’s not all the information we collected. If you read our deeper dive into DOT and diagnostic inspections, then you know we collected a lot of additional data around, well, just about everything.

Well, buckle up, because we’ve got even more unpublished data about parts, fill rates, and more to share with you today. We’ve even brought in a special guest—our friend Jimmy Wall of Donahue Truck Centers—to help us interpret some of this data and contextualize it for repair shops. So grab a coffee—and maybe a calculator—and sit back with your phone or tablet. Stuff’s about to get interesting!

Inventory Cycle Counts

In the report, we focused more on the shops that were doing inventory counts. But we wanted to know more about the operations that bypassed this step.

What does the data show us?

It turns out the biggest offenders are younger shops—those that have been in business for five years or less. “I think some business owners get busy with doing many things, and inventory falls to the not urgent list,” Jimmy says, which makes sense—especially in a shop that’s just starting out. “But shops that do not conduct an inventory or cycle counting will learn the hard way.”

Jimmy’s prediction may prove right, as our data suggests shops do age out of this behavior. The operations we surveyed that have been around between 6-12 years are most likely to count their inventory weekly.

But we saw a distinct shift in operations that had been around for two decades or more. Once they reach that age, they seem to become a little more hands-off: they favor doing an inventory count once a month or once a year. Now, these are older shops, so it’s possible that’s how they’ve always done things; it may also be an indication that they’ve put their years of experience to the task and have a process that really works for them.

Still, that process might work against them in a parts shortage. Among our respondents, those who reported the most severe disruptions due to the shortage were the shops that only counted inventory once a year.

Managing Cores

Most of the shops we surveyed are managing their cores. But as we mentioned above, we were very, very curious about those who weren’t.

Those wild and crazy younger shops (again, five years of age or below) are the primary culprits—they laugh in the face of core management (okay, that might be some editorial language). These shops also by and large aren’t doing inventory counts, which is both disappointing but maybe not surprising.

This may eventually come back to hit them in the wallet.

We found that shops not managing their cores generally fall into the lower range of annual gross revenue—69% make between $0-$1,000,000, with only 3% of shops making at least $2,000,000.

Compare this to the 47% of shops that do manage their cores. They claim revenue between $1,000,000 to $6,000,000+, with close to 26% of that section—yes, over a quarter—making at least $2,000,000 in annual gross revenue.

Shop Fill Rate

Next, we turned to shop fill rate and the question of how often shops venture outside their regular vendors. We expected the shops that maintain low inventory would be purchasing more often from new suppliers. Instead, only 32% of shops that keep low inventory (25% or less) reported such an issue.

Jimmy suggests most shops that have high volume parts sales and inventory value understand the importance of parts sales and parts availability. “These shops will usually have more advanced and skilled employees that can manage parts inventories and source parts from different vendors. A skilled shop will always try to find parts where they can in order to take care of their customers.”

Meanwhile, we found that 47% of shops that stocked 25%-50% of parts reported needing to use new vendors frequently or very frequently.

Internal Fleet vs. Indie Fleet Repair

And now we reach the dark, mysterious depths of the ocean floor.

When we compared the workings of internal fleets to independent shops, we found that fleets tend to lean towards a weekly cycle count more than indie repair shops. Fleets in general were more likely to perform cycle counts in general; only 3% of fleets had never completed one, as opposed to the 11% of independent shops.

Both types of shops faced disruptions during the parts shortage, but 17% of fleets reported a 4 on the disruption scale—that was the highest selection we received from fleet shops. In contrast, indie repair shops mostly marked a 3 on the disruption sale. This may be because fleets tend to stock more parts on the shelves so they have them. As Jimmy points out, “If a fleet is specced the same, [the repair shop] knows they will always need the same starter or filter.”

When it comes to finding new vendors, over a quarter of fleet shops (28%) told us they turned to new suppliers frequently or very frequently. This is slightly higher than the 26% of indie shops that selected the same answer options.

Why the difference? It’s hard to say. Fleets may have a higher level of urgency built into their work—they need to get trucks on the road now, so they’ll source a part wherever they can. Independent shops, however, will do what they can with the capacity (and suppliers) they have.

What does it all mean?

We’ll quote the wisdom of Irvin again: “It is easy to let inventory get out of hand.”

All these extra layers of data have told us that the situation with parts, and how repair operations handle them, remains delicate. In the old days, when parts were easy to get, a shop could still run itself into the ground if it didn’t handle inventory carefully. Today, with the global supply chain in such a precarious position, meticulous inventory management is even more important. You can get a quote from your supplier on a part they have in stock on a Tuesday, then go to order that part on a Wednesday and find out they’re completely sold out…for the next three months.

In other words, protect your inventory. Guard it like Cthulhu guards the Marianas Trench.* In times like these, it may be what saves your shop from trouble.

Whew! After looking at all this data, we have the following suggestions (bear in mind these are only suggestions—even our data has limits):

- Complete a cycle count more frequently if you only do it monthly, quarterly, or annually.

- Shops starting out should really take the time to manage their inventory and cores. We know you guys have a lot on your plate—but this habit will really, truly help you in the long run.

- If you stock a low volume of inventory and rely on just in time (JIT) delivery, understand that there are some added risks in running your shop that way right now (you probably already know this, but we figure we’ll say it anyway).

Did you like crunching these numbers with us? Then head on over to the State of Heavy-Duty Repair and see what else we learned about how modern repair shops operate!

*I’m not sure if that’s what Cthulhu does, but it seems like it’s kind of his line of work.